Article

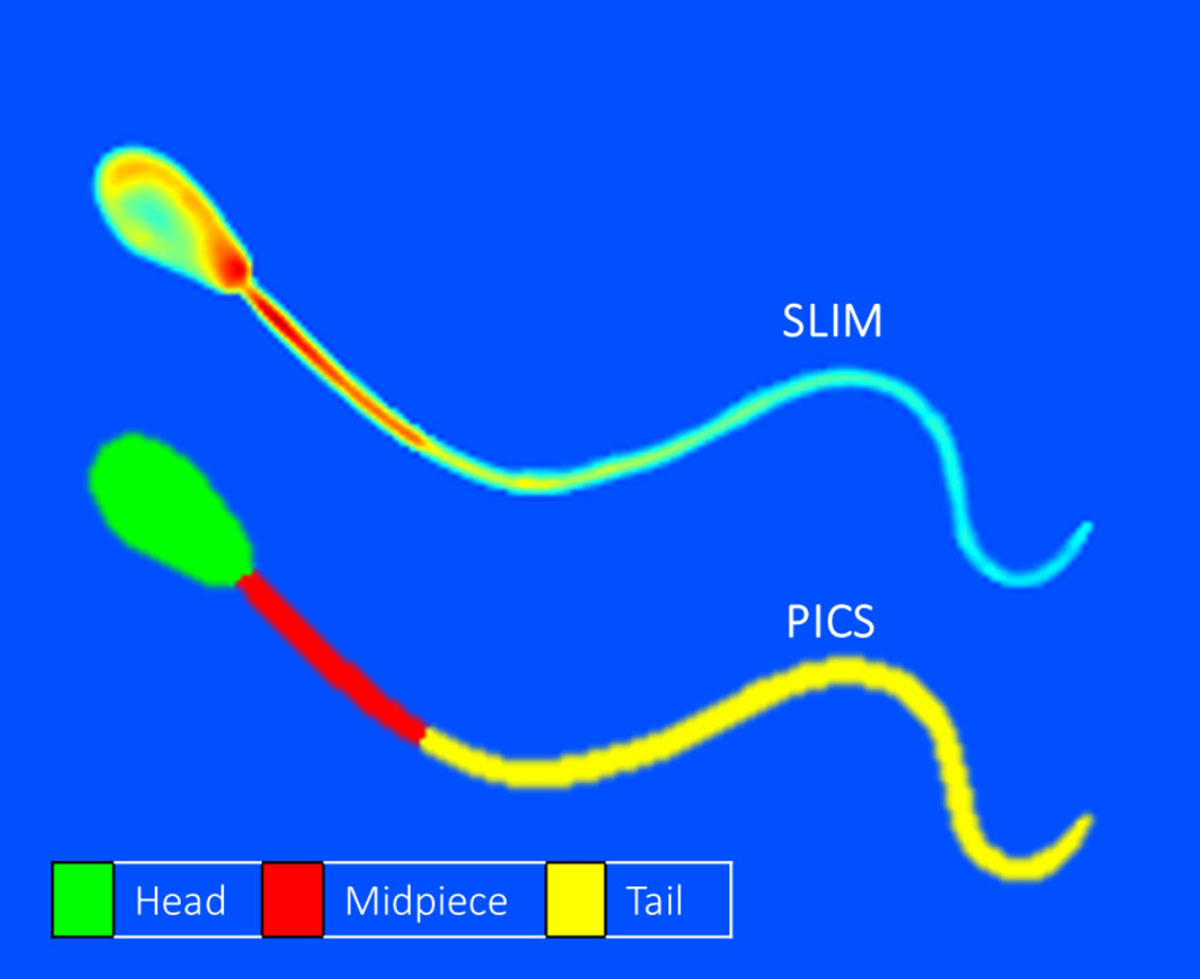

Phase imaging with computational specificity applies artificial intelligence to label-free spatial light interference microscopy data to map subcellular compartments, as illustrated.

Researchers at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology and the Department

of Animal Sciences have collaborated to develop a new technique that can be used to determine the fertility of sperm samples. They hope to further develop the technique for assisted reproductive technology in humans.

Phase imaging with computational specificity applies artificial intelligence to label-free spatial light interference microscopy data to map subcellular compartments, as illustrated.

Researchers at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology and the Department

of Animal Sciences have collaborated to develop a new technique that can be used to determine the fertility of sperm samples. They hope to further develop the technique for assisted reproductive technology in humans.

The study “Reproductive outcomes predicted by phase imaging with computational specificity of spermatozoon ultrastructure” was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This work is a part of a five-year project to develop dairy cattle that are resistant to heat and diseases in tropical areas. We want to donate these cows to developing countries to increase their food production,” said Matthew B. Wheeler, a professor of animal sciences and of bioengineering at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Matthew B. Wheeler uses embryo technologies to improve livestock production.

Matthew B. Wheeler uses embryo technologies to improve livestock production.

In order to develop these traits in cattle, the researchers need to determine which sperm samples work best for in vitro fertilization.

“Although the males may have sperm that are seemingly perfect, there could be morphological or DNA issues. This collaboration allows us to evaluate the spermatozoa and select the best in terms of fertility,” said Marcello Rubessa, a research assistant professor in the Wheeler Group.

Traditional techniques for imaging sperm samples are slow and labor intensive, and involve toxic stains. To circumvent this issue, these two teams used the label-free imaging techniques developed in the Beckman Institute’s Quantitative Light Imaging Laboratory to determine what parameters of the sperm make them fertile.

“We knew from the fertilization experiments which sperm samples worked. We used our imaging technique to understand what parameters were important for success,” said Mikhail Kandel, a graduate student with the Beckman lab. “We saw that the relationship between the size of the head and the tail of the sperm is an important parameter for fertility.”

Additionally, the researchers also improved the speed of the technique. “We used artificial intelligence to automate the process of analyzing these sperm cells,” said Yuchen He, a graduate student with QLIL.  Gabriel Popescu is interested in developing novel optical methods to image cells and tissues.

Gabriel Popescu is interested in developing novel optical methods to image cells and tissues.

The researchers hope to improve the speed of the technique for future analysis. “The motility of the sperm is sometimes fast. Therefore, we need to do the measurements quickly,” said Gabriel Popescu, a professor of electrical and computer engineering, and of bioengineering, and the director of the Quantitative Light Imaging Laboratory.

“For many years, we have developed various techniques for label-free imaging knowing that we had to give away molecular specificity,” Popescu said. “However, our newly developed phase imaging with computational specificity brings back the molecular specificity via AI, which is harmless and works on live cells. The applications are limitless, but one that truly benefits from absence of chemical stains is the assisted reproduction, as described in this collaborative study.”

The study was supported by grants from the Ross Foundation, the United States Department of Agriculture, the National Institutes of Health, and the Integrated Grants Management System.

The study “Reproductive outcomes predicted by phase imaging with computational specificity of spermatozoon ultrastructure” can be found at https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2001754117.

Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology