Bugscope, a project that was started in the first few months of 1999, allows classrooms all over the world to view a variety of insects and arthropods—from spiders to bees to mosquitos—by connecting with the Bugscope team members via a web interface that allows them to view images in real time, chat, and operate the scanning electron microscope (SEM) in the Microscopy Suite. Initial funding for the project came from the National Science Foundation, the Lumpkin Family Foundation, IBM, and Submeta.

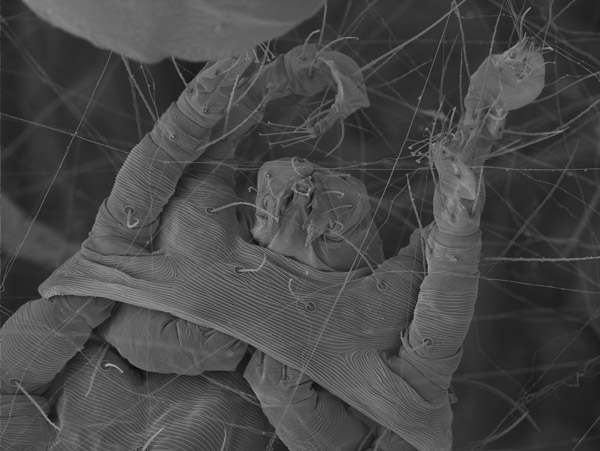

Live interactive control of the SEM is available through any web browser. Students mail bugs to the Microscopy Suite, and staff members create a unique sample for that class. Teachers can choose to log in from a single computer connected to a projector, or students can log in individually to easily participate in the discussion. The live interface allows all participants to see the latest images coming from the microscope, ask questions via the built-in chat interface, and have the opportunity to control the microscope.

Fifteen years ago, the capabilities of Bugscope were revolutionary. Within five years of the advent of the very first website (put up by Tim Berners-Lee in 1992), the Imaging Technology Group at the Beckman Institute had developed its first web-based educational outreach project, called Chickscope. Part of a collaboration with Paul Lauterbur, who would win the Nobel Prize for his pioneering work in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), Chickscope utilized MRI to collect and deliver, via the web, images of chicks as they developed within their egg shells. A tiny number of classrooms had live access to those images, and the project tallied several thousand dollars in costs.

Having garnered useful information from Chickscope, as well as from the implementation of web-based control of a transmission electron microscope, in 1998 Clint Potter and Bridget Carragher (at that time the co-directors of the Imaging Technology Group), conceived of an affordable, sustainable educational outreach project, to be called Bugscope. With the support of key faculty members at the University of Illinois, they wrote a successful NSF proposal that allowed them to purchase a high-resolution scanning electron microscope. The $600,000 microscope would be utilized in a wide variety of research at the university as well as providing the basis for Bugscope.

We absolutely love when students ask a lot of questions. Sessions can get pretty crazy, with students asking a million different questions, but we encourage it. We want them to be engaged in what they’re seeing. - Scott Robinson

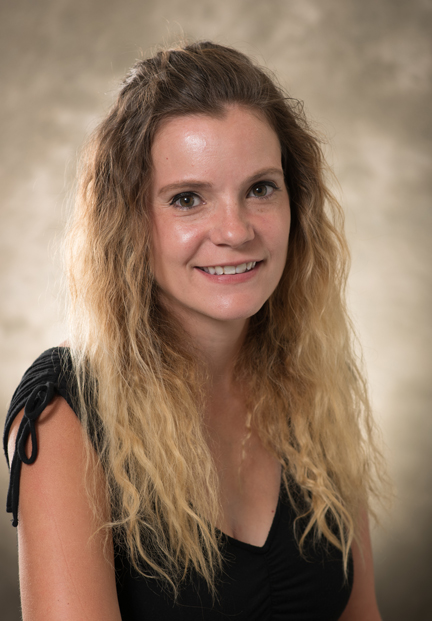

Scott Robinson was hired in November 1998 to help install and operate the new microscope; his other primary task was to serve on the team that would make the Bugscope concept a reality. The team worked quickly, and the first official Bugscope session was held on March 19, 1999, with a local school.

To put things in perspective, when the Bugscope project went online, the web was much more primitive than it is today. Bugscope predates Wikipedia and Facebook, and on the day of the first official Bugscope session, Google had only eight full-time employees.

In the intervening years, the Bugscope interface has been updated three times, but the original spark is still there.

“We absolutely love when students ask a lot of questions,” Robinson said. “Sessions can get pretty crazy, with students asking a million different questions, but we encourage it. We want them to be engaged in what they’re seeing.”

Last year, the Oprah Winfrey Leadership Academy (OWLA) for Girls in Henley, South Africa, participated in a Bugscope session. Despite the seven-hour time difference, staff members at Beckman were available to chat live with the 8th grade class.

Because of customs control, the girls were unable to send samples of insects, so the Microscopy Suite provided some. The OWLA girls viewed an ant, mosquito, silverfish, wasp, roly poly, and spider, among other insects/arthropods.

The girls had several questions, such as, “Why do we itch when a mosquito bites us?” “How long do insects live?” and “Do ants have brains?”

“It’s truly inquiry-based learning,” Robinson said. “We want the kids to get interested in science as a career, so when we’re answering questions, we’re always patient, and we’re careful to address them as equals—we don’t want to ‘talk down’ to them. It’s especially cool when they ask what we do in our jobs or what schooling we had to do to become scientists. That’s when you know they’re really enjoying learning.”

To prepare a specimen for a sample, the bug is frozen for a few days, allowed to thaw and dry, and then coated in gold-palladium—creating stunningly crisp and detailed electron microscopic images.

The Bugscope Project has conducted more than 800 sessions in 15 years, and staff members continue to share the SEM with classrooms every week. Robinson is glad to provide Bugscope as a unique outreach service.

“We hope to continue it for many years to come,” said Robinson. “It’s all about the kids.”