Article

Lydia Kisley. Credit: Matt Shiffler.

Lydia Kisley. Credit: Matt Shiffler.The date was Monday, Sept. 19, 2016, and the Beckman Auditorium’s third-row-center seat had never held a more enthusiastic audience member.

Lydia Kisley perched on its edge, captivated by a speaker just two years away from receiving the Nobel Prize in Chemistry: Frances Arnold, nationally renowned chemist and Caltech professor.

“I felt like I was watching a movie, not an academic lecture,” said Kisley, who is now the Warren E. Rupp Assistant Professor of Physics at Case Western Reserve University. “How Arnold talked about her science grabbed my attention in a way that science talks rarely do. So many scientific presenters default to data-dumping, but Arnold’s talk wasn’t like that. She let go of the details at the start, took a big picture view, and led with her passion.”

This spring, Kisley took a similar approach when she delivered the 2023 Kavli Foundation Emerging Leader in Chemistry Lecture at the American Chemical Society’s March meeting.

“I wanted to tap in to why we spend years studying chemistry, and hours each week thinking about it,” Kisley said. “If I could convey a fraction of the passion Arnold had in her talk, that would be a success.”

So, Kisley resisted diving into the details — at least right away. She stepped lightly around terms weighted down with academic jargon. And, of course, she put her passion first.

“It’s all about the microscopes”

Kisley delivers the Kavli Foundation Emerging Leader in Chemistry Lecture at the American Chemical Society's spring meeting in March 2023.Kisley’s talk was billed as “Seeing the molecular world of materials: Single-molecule microscopy at the crossroads of chemistry.” True to its title, it focused on her twin passions: microscopy and chemistry. Kisley's research happens where the two converge.

Kisley delivers the Kavli Foundation Emerging Leader in Chemistry Lecture at the American Chemical Society's spring meeting in March 2023.Kisley’s talk was billed as “Seeing the molecular world of materials: Single-molecule microscopy at the crossroads of chemistry.” True to its title, it focused on her twin passions: microscopy and chemistry. Kisley's research happens where the two converge.

“When I tell people about my career, I don’t lead with the chemistry part,” she said. “Instead, I say that I shoot lasers at things to look at them at small scales. It catches people’s attention.”

Microscopy is Kisley's window into the complex chemical reactions that pop, hiss, and change color to myriad ends. It’s also the backbone of her lab at Case Western Reserve University. Kisley and her colleagues build and design innovative microscopic technologies which use beams of light (so-called lasers) to illuminate molecules: the universe’s personal set of pint-sized Lego bricks.

Since molecules make up all chemical reactions, microscopy is the researchers’ pivot point between a slew of chemistry subfields.

“It’s not necessarily important to me if our work is classified as industrial chemistry, analytical chemistry, or even another academic department altogether,” Kisley said. “I just want to put cool stuff in the microscope and be open to discovery.”

For example, an ongoing project uses microscopy to study corrosion, the unsightly chemical handshake between iron, oxygen, and water molecules that results in rust. Researchers in the lab can study corrosion more quickly and safely than in the real world, and their observations help evaluate anticorrosive substances and protect infrastructure.

While most people are familiar with the orangey sheen of a rusty bike lock or a penny’s verdant verdigris, Kisley also studies the chemical infrastructure inside our bodies. Microscopy helps her to analyze how proteins move through the nanoscale network of hallways — called the extracellular matrix — to deliver materials from cell to cell. Understanding how the proteins behave in this environment helps clinicians design safe, protein-based packages for shipping drugs and therapeutics into the body.

“We’re looking at diverse materials, so our applications are diverse as well, and impact various sectors,” Kisley said. “The work on corrosion pulls from analytical chemistry and industry, and the work on the extracellular matrix is connected to biology and medicine. The unifying factor is the microscopes we're developing — it’s all about the microscopes. They tie everything together.”

Saying no to silos

Kisley’s appreciation for the microscopic world began during her undergraduate years at Wittenberg University. She still remembers stepping up to a microscope loaded with nanoparticles:

“That moment was intriguing for me. As chemists, we’re trained to think on a molecular scale, but the methods we use are based on averaged measurements and data — we don’t get to see that molecular world. Microscopes allow me to see the world in the way that I was trained to think,” she said.

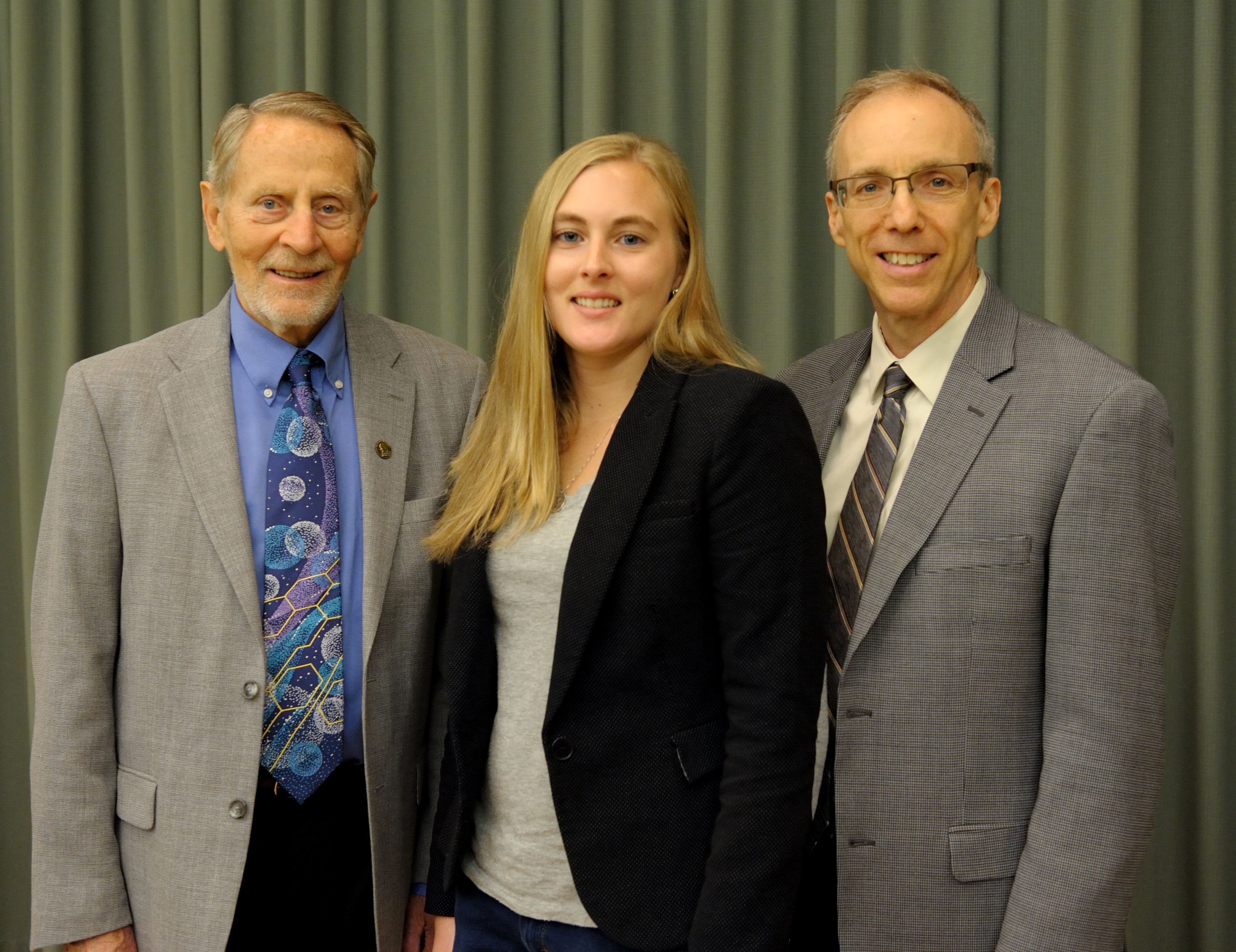

Lydia Kisley with Beckman Institute Founding Director Ted Brown (left) and Jeff Moore (right), the director of the Beckman Institute during Kisley's postdoc.

Lydia Kisley with Beckman Institute Founding Director Ted Brown (left) and Jeff Moore (right), the director of the Beckman Institute during Kisley's postdoc.Kisley’s chemistry education became permanently linked to microscopy. In 2010, she obtained her bachelor’s degree in chemistry; in 2015, she earned her Ph.D. from Rice University in physical chemistry with a focus on single-molecule microscopy; in 2016, she accepted the inaugural Beckman-Brown Interdisciplinary Postdoctoral Fellowship at the Beckman Institute, where she layered on even more interdisciplinary components.

“At Beckman, I began to build up my confidence and independence as a researcher,” Kisley said.

During her postdoc, Kisley collaborated with chemistry professor Martin Gruebele, chemical and biomolecular engineering professor Deborah Leckband; and materials science and engineering professor Paul Braun.

“Lydia is exceptional in many ways, but two things stand out for me,” Leckband said. “First, she has an exceptional ability to pull together ideas and approaches from different disciplines to solve real world problems in unique and elegant ways. Second, she has a very clear view of what she wants to achieve and how to get there.”

Kisley pictured with a copy of the Forbes 30 Under 30 list, on which she appeared in 2017.

Kisley pictured with a copy of the Forbes 30 Under 30 list, on which she appeared in 2017.Kisley’s research interests at the Beckman became the bedrock of her future career. Her microscopic analysis of protein dynamics — and its applications in biomedicine — earned her a spot on the 2017 Forbes 30 Under 30 – Healthcare list. But Kisley’s work at Beckman didn’t just garner national media mentions — it also bolstered her confidence as a cross-disciplinary chemist.

“During my time at the Beckman, I was exposed to so many different areas of science that you aren’t usually able to get at a single institution. That experience expanded my horizons in fields of science that I wasn’t aware of before. It touches my research even now,” Kisley said.

“If I wasn’t at the Beckman Institute, my research program would be completely different.”

Crossroads chemistry

As a faculty member at Case Western Reserve University, Kisley continues to merge disciplines and resist traditional scientific silos. Case in point: the chemist’s office is located in the Physics Department.

“When I meet people, I have that internal debate over how I’m going to describe what I do. My Beckman background empowers me to say: ‘I can do chemistry, and I can do physics, too,’” she said.

Looking ahead, Kisley will continue to fuse microscopy, chemistry, and more into a self-proclaimed “hot mess of different fields.” For example: stretching materials under a microscope with mechanics, a discipline that she “didn’t even know her field could intersect with until [her] time at Beckman.

“With microscopy, we can improve our collective understanding of so many different elements of the world around us, and we can see so much that we couldn’t otherwise,” she said.

This is the big picture that Kisley hoped to convey through her Kavli Lecture — inspired, of course, by Frances Arnold.

“If I had a time machine, I’d go back and tell my postdoc self that it’s all going to work out,” Kisley said. “I was so worried about whether I’d be able to pursue the research I wanted to. But I think that hard work, and really caring about the science — that’s what it’s all about.

“That’s the big picture for me, and it pays off.”

Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology