Article

An early portrait of Mabel Meinzer Beckman. Courtesy of the Beckman Foundation; used with permission.

An early portrait of Mabel Meinzer Beckman. Courtesy of the Beckman Foundation; used with permission.

Mabel Beckman learned to drive in 1926, kicking dust clouds across the Wyoming countryside in a Model T Ford. Arnold, her husband of a year, dozed beside her as the trusty two-speed lurched westward from Brooklyn to the California coast. If the newlyweds’ life was to be a shared experience, Mabel reasoned, so should the driver’s seat.

And so would the Arnold O. and Mabel M. Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, founded 60 years later at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. The history of the institute is incomplete without the richly layered biography of Mabel Beckman, who partnered with her husband in friendship, family, business, and philanthropy for 70 years. Her sage wisdom, iron will, and steadfast work ethic influenced the institute’s inception and continue to guide its focus today.

Mabel Meinzer canoeing with friends. Courtesy of the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation; used with permission.

A lifelong Brooklynite

Mabel Meinzer canoeing with friends. Courtesy of the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation; used with permission.

A lifelong Brooklynite

Mabel Meinzer was born in Brooklyn, New York, on Dec. 20, 1900, taking her first steps as the nation toddled into the 20th century. A middle sibling between two brothers, Mabel fit snugly into her family of five in their home on Oakton Street. Brooklyn was the backdrop to Mabel’s most formative years, from high school graduation to the year spent studying art at the Pratt Institute. Unbeknownst to her, the borough would also play a pivotal role in Mabel's adult life — i n fact, a humble Brooklyn barracks was destined to deliver her future husband to her doorstep.

Mabel in her Salvation Army nurse's uniform. Courtesy of the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation; used with permission.

A committed public servant

Mabel in her Salvation Army nurse's uniform. Courtesy of the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation; used with permission.

A committed public servant

“It’s funny, growing up they were just ‘grandma and grandpa,’” said Arne Beckman, grandson to Arnold and Mabel. “[I] had no real idea what they had accomplished until [I was] older.”

Even before their dynamic partnership began, Mabel Meinzer and Arnold Orville Beckman shared common ground. Both were born in 1900, Mabel in the Big Apple and Arnold in small-town Illinois; their paternal grandparents had immigrated to the U.S. from Germany; and they shared a flair for the fine arts, though Mabel preferred oils and needlework to Arnold’s chosen instrument, the piano.

But it was their twin commitment to service that prompted a serendipitous union on Thanksgiving Day 1918. Mabel, a Red Cross nurse at the time, had volunteered to serve Thanksgiving dinner to the troops at a local YMCA. In walked Private Beckman, a Marine nearing the end of his term. After the meal, Arnold asked if he might escort Mabel home; sparks flew through the chilly November evening as they headed back to the house on Oakton Street.

“One thing that shined through was their love for each other,” Arne Beckman said. “They were two peas in a pod. Never a harsh word between them.”

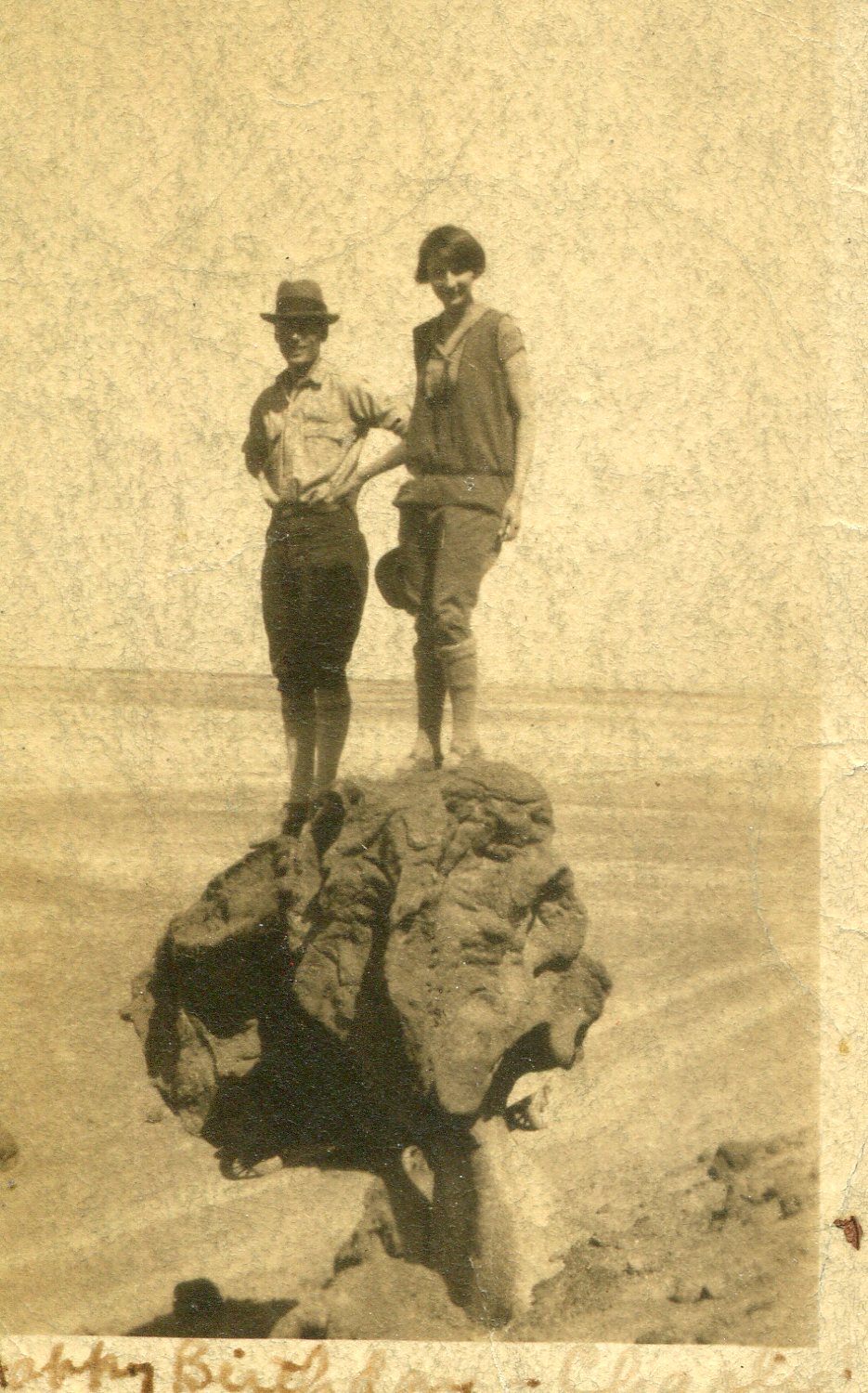

The Beckmans adventuring through Death Valley in the 1920s. According to Mabel's grandson Arne Beckman, this image "captures [Mabel's] spirit perfectly." Courtesy of Arne Beckman.

An adventurous spirit

The Beckmans adventuring through Death Valley in the 1920s. According to Mabel's grandson Arne Beckman, this image "captures [Mabel's] spirit perfectly." Courtesy of Arne Beckman.

An adventurous spirit

With his military service complete and college looming, Arnold was off to Urbana-Champaign by the following fall. Nevertheless committed, the young couple faced years of long-distance courtship with conviction and a stack of postage stamps.

Mabel stayed in Brooklyn and worked as an executive secretary and clerical supervisor. Arnold completed his bachelor’s and master’s degrees at UIUC and began his doctoral work at the California Institute of Technology. Sealed envelopes flurried across the continent for almost six years. In 1924, Arnold paused his Ph.D. to move back east; the couple married in Brooklyn on June 10, 1925. Though long-awaited, their wedding was bittersweet, as it signaled Mabel’s farewell to her hometown.

In fall 1926, with the words “Oh baby, just married” barely scrubbed from the door of their Model T, the young couple pooled their paychecks and departed for Pasadena, where Arnold would complete his Ph.D. at Caltech. Compared to six years of long-distance dating, the six-week road trip was a cinch. Mabel learned to drive on Wyoming’s winding roads; Arnold broke a personal record for 19 tire-changes in 24 hours; the couple forded the Snake River, camped in canvas tents, and cultivated a lifelong affinity for the outdoors.

“Their adventurous spirit was contagious, and all of us grandkids caught the bug,” Arne Beckman said.

Courtesy of the Science History Institute's Beckman Historical Collection.

Courtesy of the Science History Institute's Beckman Historical Collection.

"The consummate entertainer"

Fresh from their quest across the continent, Arnold and Mabel seized a new adventure in the 1930s: starting a family. They built a house in Altadena, California, and adopted two children — Patricia and Arnold — to make it a home.

Interrupted only by Mabel’s seven-month tussle with tuberculosis, the Beckmans assumed a steady rhythm during a decade otherwise occupied by the Great Depression. Per her personal ritual, Mabel rose with the sun each morning, and Arnold’s commute ferried him daily to Caltech. Unfailingly, the couple shared their midday meal. They also shared their household duties: Arnold tended to his rose garden and tackled various home improvement projects; and Mabel managed all facets of the household and prepared nutritious dishes for family and friends.

“She was the consummate entertainer and hosted presidents and other politicians [and] business leaders. … She did the cooking herself for these occasions, and when asked, she would say something like, ‘Oh yes, we had some friends over for supper,’” Arne Beckman said.

Soon, the century would give rise to the sentiment that “behind every great man is a great woman.” This did not seem to apply to the Beckmans.

“She never stood ‘behind’ grandpa and was always his sounding board and main business confidant,” Arne Beckman said. “I don’t think people give her enough credit for her wise counsel to our grandpa over their lifetimes. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to appreciate her strength, and what it meant to the family, even more.

“I don’t think he would have been nearly as successful without her by his side.”

A collaborator and confidant

Mabel remained her husband's unflagging conscience and stalwart sounding board.

The decades following the Beckmans’ move to Altadena were studded with Arnold’s professional and scientific milestones of highest acclaim; among them, the invention of the pH meter and foundation of National Technical Laboratories, which would

one day become the world-renowned Beckman Instruments, Inc., and later, Beckman Coulter. Through it all, Mabel was her husband’s unflagging conscience and stalwart sounding board.

Mabel remained her husband's unflagging conscience and stalwart sounding board.

The decades following the Beckmans’ move to Altadena were studded with Arnold’s professional and scientific milestones of highest acclaim; among them, the invention of the pH meter and foundation of National Technical Laboratories, which would

one day become the world-renowned Beckman Instruments, Inc., and later, Beckman Coulter. Through it all, Mabel was her husband’s unflagging conscience and stalwart sounding board.

“There was never a feeling of ‘He’s the businessman and she’s his wife,’” Arne Beckman said. “They were true equals and lived their lives that way always. She was demure but at the same time had an iron will and a steel backbone.

“Their success was a close collaboration between two people who loved and respected each other greatly.”

But even as the business grew in acclaim and transcontinental air travel replaced camping trips in the Model T, the Beckmans were never far from their next foray into the unfamiliar.

A canny philanthropist

Fifty years after the Beckmans angled out west, autumn flushed down the California coast and the couple contemplated their next adventure. They incorporated the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation in September 1977, two years after their golden anniversary.

Though the foundation was established to disperse the profit turned by Beckman Instruments, Inc., its execution was personal. Arnold and Mabel managed the foundation’s operations from their home in Corona Del Mar, California, supported by secretary Jane Guilarte. Mabel’s unofficial advisory role swiftly solidified into a secretarial position on the foundation board, wherein she sagely assessed countless streams of proposals, attended numerous meetings and site visits, and exercised discernment in the face of difficult gift-giving decisions. So extensive and integral were her duties that Arnold added several members in her place after her passing.

The Beckmans wielded the foundation in service of projects that reflected their personal commitments. Their investments furthered basic science, supported young investigators, and advanced medical research. In remembrance of Mabel’s bout with tuberculosis, they gave their first major gift to the City of Hope National Medical Center, which originated in the 1910s as a tuberculosis clinic. The Beckmans made five subsequent mega-gifts between 1978 and 1989.

A proposal from her husband’s alma mater caught Mabel’s eye early on.

A Fighting Illini (in Pasadena)

Arnold and Mabel Beckman with Stanley O. Ikenberry in front of a bronze statue of Arnold, which is located today at the Beckman Institute.

On Jan. 1, 1985, the Fighting Illini played the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California. To celebrate, radios blared out a Beach Boys parody playfully titled “The Fightin’ Illini in Pasadena.” Fittingly, this title was also appropriate

for Mabel Beckman, who — eighty-four years old at the time — cheered on the orange and blue from the stands.

Arnold and Mabel Beckman with Stanley O. Ikenberry in front of a bronze statue of Arnold, which is located today at the Beckman Institute.

On Jan. 1, 1985, the Fighting Illini played the Rose Bowl in Pasadena, California. To celebrate, radios blared out a Beach Boys parody playfully titled “The Fightin’ Illini in Pasadena.” Fittingly, this title was also appropriate

for Mabel Beckman, who — eighty-four years old at the time — cheered on the orange and blue from the stands.

The summer prior, then-president of the university Stanley O. Ikenberry had proposed that the Beckman Foundation support an interdisciplinary research institute on the Urbana campus — what would one day become the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. The Beckmans attended the game with Stan and his wife, Judy, and the event sparked an enduring friendship between the two couples.

“My first impression of Mabel was that she was a constant companion of Arnold, but that Arnold was the center of the spotlight,” Stan Ikenberry said.

“As we got to know [the Beckmans] better, we realized that Mabel was a force of her own, and had a great influence on Arnold, and that they generally made all of their big decisions together. She was very influential, but never took the spotlight.”

Mabel’s influence was especially valuable when it came to the university's proposal.

.jpg?Status=Master&sfvrsn=188752fc_1) Mabel Beckman (third from right) participates in the Beckman Institute's groundbreaking ceremony in 1986.

“I was walking into Arnold’s office with Mabel … [looking] at the various proposals on Arnold’s desk,” Stan Ikenberry said. “Mabel must have seen me doing that, and maybe detected a little bit of anxiety

and depression in my face, and she put her arm around me and said, ‘Stan, don’t worry. Arnold likes Illinois best.’ I walked away fairly comfortable and assured that this was going to work out.”

Mabel Beckman (third from right) participates in the Beckman Institute's groundbreaking ceremony in 1986.

“I was walking into Arnold’s office with Mabel … [looking] at the various proposals on Arnold’s desk,” Stan Ikenberry said. “Mabel must have seen me doing that, and maybe detected a little bit of anxiety

and depression in my face, and she put her arm around me and said, ‘Stan, don’t worry. Arnold likes Illinois best.’ I walked away fairly comfortable and assured that this was going to work out.”

And work out it did: the Beckmans ultimately contributed $40 million toward the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology.

“If Mabel had not been on board,” Stan Ikenberry said, “I’m pretty sure that Arnold would not have made the gift.”

Mabel frequented the site of the Beckman Institute from its groundbreaking in 1986 to its dedication in 1989, asking questions and observing the construction process all the while. Her final visit to the institute honored its inauguration in April 1989, and she passed away in California three months later, at 88 years old.

An empathetic friend

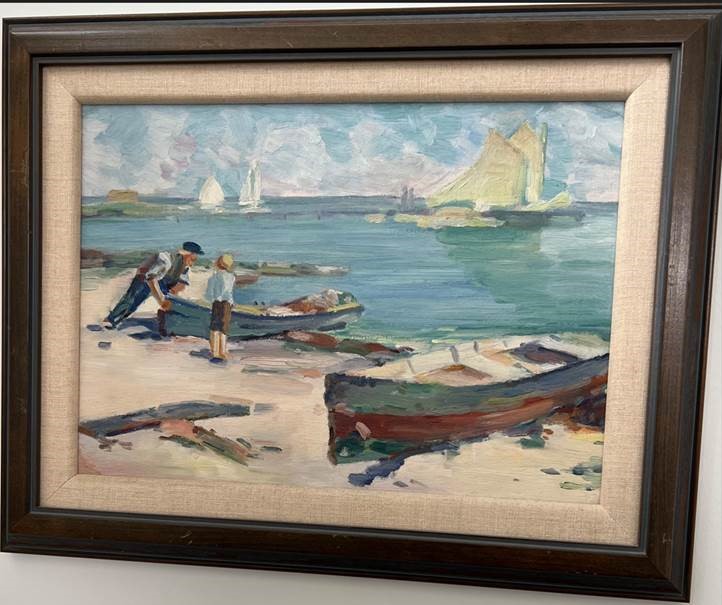

Mabel Beckman was a talented artist. One of her last surviving oil paintings, created in 1936, hangs proudly in the home of her grandson, Arne Beckman. Courtesy of Arne Beckman.

Adventurous spirit. Gifted artist. Witty and wise. Canny and kind. Each might be used with equal accuracy to describe such a dynamic figure as Mabel Beckman.

Mabel Beckman was a talented artist. One of her last surviving oil paintings, created in 1936, hangs proudly in the home of her grandson, Arne Beckman. Courtesy of Arne Beckman.

Adventurous spirit. Gifted artist. Witty and wise. Canny and kind. Each might be used with equal accuracy to describe such a dynamic figure as Mabel Beckman.

Years later, though, Judy Ikenberry recalls an instance of Mabel's kindness and empathy, particularly in support of women whose influence took place behind the scenes.

“It was the commencement weekend, in which Arnold was given an honorary degree and gave the commencement address, and [the Beckmans] were our houseguests,” she said. “I worked very hard in my mind to think about how the four of us could have dinner … after commencement. … I came up with a cold supper. Mabel looked at me, saw how tired I was, … and said, ‘Judy, this is just too much!’ And I thought: ‘She knows how tired I am, and she cares.’

“[It’s] a really sweet memory that ... I think demonstrates her empathy with me as another woman who was a partner and working hard. She understood what I was doing.”

Sources and additional reading:

- "Arnold O. Beckman: 100 Years of Excellence" by Arnold Thackray and Minor Meyers, Jr.

- "Bridging Divides: The Origins of the Beckman Institute at Illinois" by Ted Brown

- The Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation website

- The Science History Institute's digital photo archives

Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology