Article

The human brain's complex infrastructure, also known as the functional connectome, constantly rearranges itself to make connections across distant brain regions. Illinois researchers found that certain time-based characteristics of the connectome, like how often its configuration changes, can be inherited from one generation to the next.

“Our study demonstrates that spontaneous, moment-to-moment changes in cross-region connectivity can be inherited. This may contribute to differences in cognitive abilities between individuals,” said Sepideh Sadaghiani, the study's principal investigator and the leader of the CONNECT Lab at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology.

In the past, researchers have used functional MRI data to identify inherited properties of the time-averaged, or static, connectome. But static analyses of dynamic brain processes can only ever tell part of the story.

Sepideh Sadaghiani (left) and Suhnyoung Jun (right) used functional MRI data to discover that some characteristics of the brain's infrastructure can be inherited from one generation to the next.

“The brain is not static. The spatial patterns of synchronization of activity across the brain — or functional connectome states — are always changing,” said Suhnyoung Jun, a psychology graduate student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the study's

lead author.

Sepideh Sadaghiani (left) and Suhnyoung Jun (right) used functional MRI data to discover that some characteristics of the brain's infrastructure can be inherited from one generation to the next.

“The brain is not static. The spatial patterns of synchronization of activity across the brain — or functional connectome states — are always changing,” said Suhnyoung Jun, a psychology graduate student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and the study's

lead author.

Changes to the functional connectome occur continuously, even when the brain is task-free, or unprompted by external stimuli, the researchers said.

"We’re learning that there is a temporal pattern of transitions between states, or the length of stay in each state, and that such patterns found in the task-free brain are under genetic influence," Jun said.

The study, which was published in NeuroImage, leveraged existing data from the Human Connectome Project, a multi-institutional collaboration that aims to map all the functional neuron connections in the brain. This project collected functional MRI data and measurements of cognitive function for over one thousand participants.

“The dataset includes sibling pairs and twins, which allows us to test how the time-based characteristics of the functional connectome can be inherited,” Jun said. “Simply put, we can test whether more genetically similar pairs of individuals, like identical twins, have more similar patterns compared with less genetically similar pairs of individuals, like fraternal twins or non-twin siblings.”

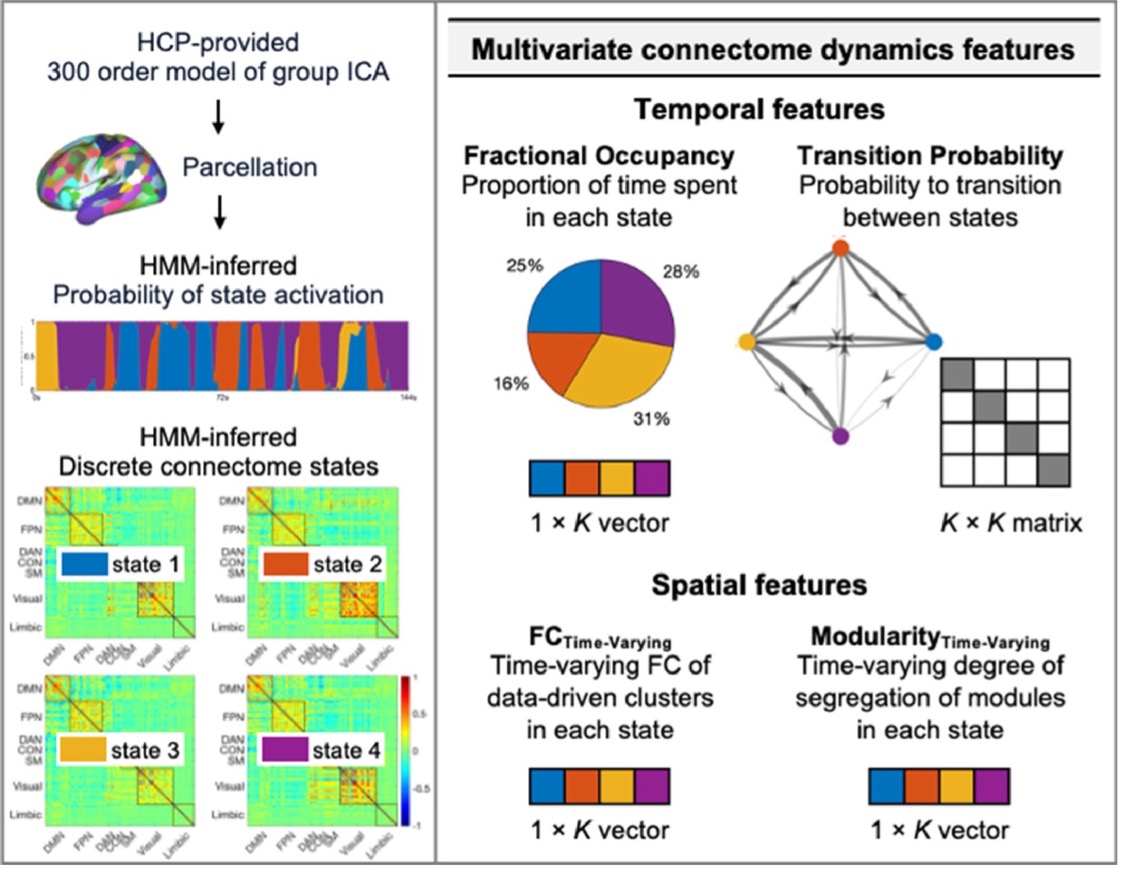

Overview of the first part of the analysis pipeline, involving selection of heritable features. Data from the Human Connectome Project was analyzed using hidden Markov models to infer discrete, recurring patterns of connectivity, leading to the selection of temporal

and spatial features for further analysis. This image is adapted from the authors' original manuscript.

Overview of the first part of the analysis pipeline, involving selection of heritable features. Data from the Human Connectome Project was analyzed using hidden Markov models to infer discrete, recurring patterns of connectivity, leading to the selection of temporal

and spatial features for further analysis. This image is adapted from the authors' original manuscript.

Jun and colleagues found that the temporal, or time-based, characteristics of the connectome states have behavioral significance. In other words, genetic effects impact the dynamic trajectory of connectome state transitions, and such temporal characteristics

may play a role in the link between the genotype and cognitive abilities.

“These findings also support a broader, ongoing shift in how neuroscientists view the brain," said Sadaghiani, a Helen Corley Petit Scholar in the UIUC College of Liberal Arts & Sciences. "Instead of primarily being a reflexive organ, most brain activity is believed to be intrinsic, shaping how we perceive and react to external events rather than simply reflecting them."

In the future, the researchers hope to study how specific genes and polymorphisms are involved with reconfigurations in the brain's connectome and make up features that can be inherited.

“For now, we know that transitions in the dynamic brain are related to genetic material,” Jun said. “This opens up a lot of questions we now want to answer related to which genes are responsible for this heritability.”

Editor's notes:

The paper “Dynamic trajectories of connectome state transitions are heritable” can be accessed at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2022.119274

More information on the NIH Human Connectome Project and associated dataset can be accessed at: http://www.humanconnectomeproject.org

For full author information, please consult the publication.

The authors declare no competing interest.

Media contact: Jenna Kurtzweil, kurtzwe2@illinois.edu

Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology