The Beckman Institute Graduate Student Seminar Series presents the work of outstanding graduate students working in Beckman research groups. The seminar starts at Noon in Beckman Institute Room 1005 and is open to the public. Lunch will be served.

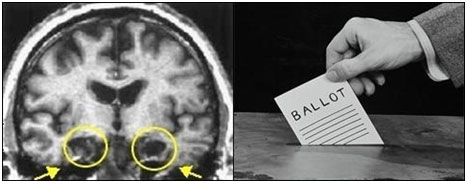

If citizens with severe brain lesions can make rational voting decisions, then so can everybody else.

Jason Coronel

Political scientists have traditionally assumed that in order for a voter to render reasonable like or dislike judgments about a given candidate, the voter must first be able to consciously recollect information about the candidate (e.g., the candidate's issue positions). Yet extensive research in public opinion has shown time and time again that most Americans possess very little to no explicit political knowledge about politicians holding or running for office. However, candidate evaluation can also be based on implicit memory processes. In this account, voters extract affective information from items they encounter about politicians. (e.g., negative affect from a candidate whose issues diverge from the voter's political preferences). When the citizen is later queried about a particular candidate, he or she only has to recall the affective information associated with the politician. As such, citizens can presumably render accurate affective judgments about a certain candidate even if they cannot explicitly recall any of the politician's issue positions. This study will determine whether citizens can vote for the candidate who most closely resembles their issue positions even if such voters cannot explicitly recollect any of the candidate's issue positions by using amnesic patients as research participants.

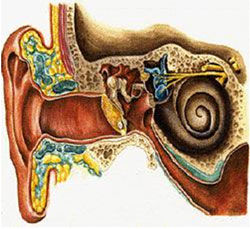

Speech perception in normal and hearing-impaired ears

Riya Singh

The Human Speech Recognition (HSR) Group at Beckman Institute focuses on understanding speech perception in normal and hearing impaired listeners, through psychoacoustic experiments. Cochlear hearing loss i.e. damage to the inner ear is the most common form of hearing loss in developed countries. This talk will focus on how each hearing-impaired (HI) ear can be characterized by using speech perception tests based on syllable (CV) confusions. We will show how the CV perception tests shows that all NH listeners are the same, while it clearly classifies the HI ears into groups. Current speech perception tests rely on average word scores, but our research shows that this is not an effective technique as each HI ear has its own consonant dependence. That is, there are only a few numbers of sounds that a HI ear cannot hear and any good hearing-aid fitting technique must concentrate on enhancing these difficult sounds, without affecting the sounds that the ear can hear.

Why do your lips move when you think?

Gary Oppenheim

I am investigating Watson’s (1913) claim that cognition is “nothing more than motor habits in the larynx.” The strongest version of the claim was disproved long ago, but one can still see it reflected in current discussions of embodied cognition. I'll specifically examine whether inner speech – which many people identify with thought – is formulated in terms of oral articulations. During overt speech production, speakers cannot simply retrieve a word – they must convert the abstract word into a pattern of muscle movements. And particular stages in speech production are associated with specific speech error patterns. Overt speech errors tend to create words (lexical bias) and involve similarly-articulated sounds (phonemic similarity effect), two phenomena that have been localized to a lexical-phonological level and an articulatory-feature level, respectively. I will present two experiments that use tongue-twisters to elicit “slips of the tongue” in inner speech. The resulting error distributions suggest that the experience of inner speech is fixed to a phonological level of representation, but can also integrate articulatory specification, perhaps through feedback. That is, inner speech is not necessarily formulated in terms of articulations, but is flexible enough to incorporate this information when becomes available.